The NY Review of Books published an in depth profile of O'Sullivan in the most recent edition of the magazine. Quite an interesting read. I never knew of the tough experiences he had (the incarceration of his father and mother).

The author also provides thought provoking analysis about the physical genius of a player like O'Sullivan and other great athletes:

www.nybooks.com

www.nybooks.com

The author also provides thought provoking analysis about the physical genius of a player like O'Sullivan and other great athletes:

Angles of Approach | Sally Rooney

What makes Ronnie O’Sullivan the greatest player in the history of snooker? It isn’t just statistical dominance—it lies in his style, in the difference between thinking and acting.

Angles of Approach

Sally Rooney

March 27, 2025 issue

Ronnie O’Sullivan is the greatest snooker player in history—what he can do, no one has ever been able to do. And no can even explain how he does it.

Reviewed:

Unbreakable

by Ronnie O’Sullivan

London: Seven Dials, 262 pp., $19.99 (paper)

Ronnie O’Sullivan: The Edge of Everything

a documentary film directed by Sam Blair

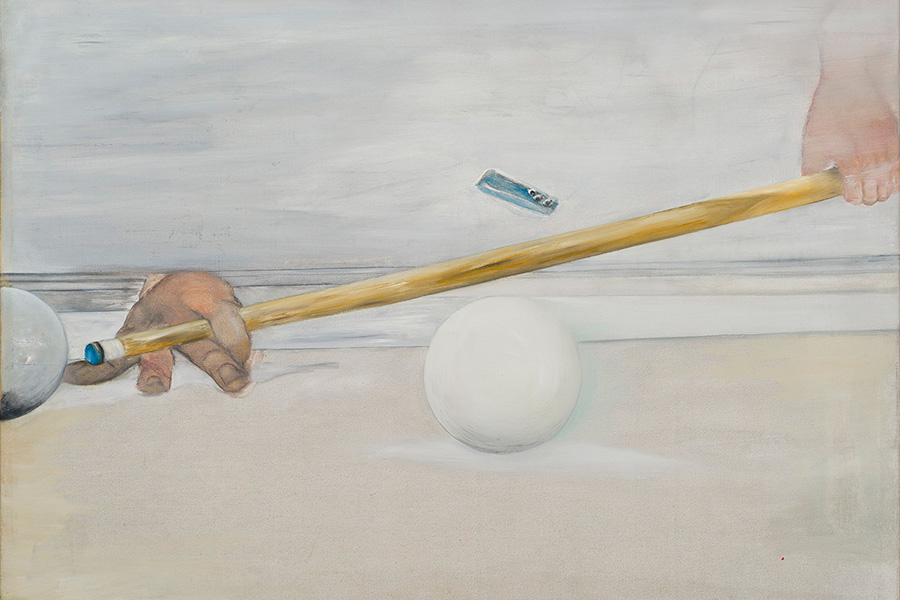

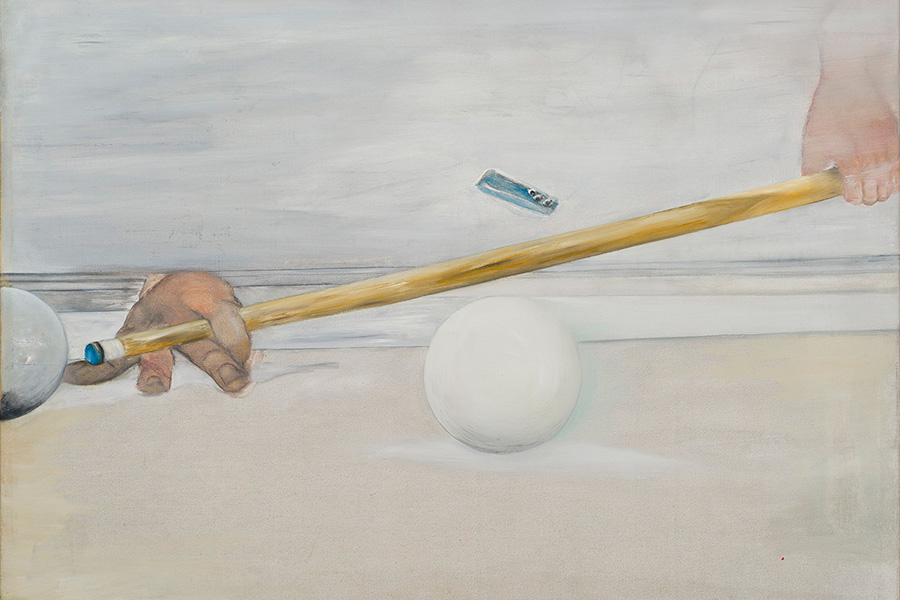

Ask almost any snooker fan to name the greatest player in the history of the sport, and they will tell you it’s Ronnie O’Sullivan. This isn’t really a matter of facts and figures, although O’Sullivan, whose professional career has now spanned over thirty years, does indeed come out on top by almost any statistical measure. If you really want to know why he’s considered the greatest, you have to watch him play the game.

Snooker is related to, but distinct from, other cue games like billiards and eight-ball pool. One key difference between snooker and pool is that snooker tables are bigger. A lot bigger. Two reasonably tall men could lie down end to end along the length of a snooker table and still not reach the corners. A standard pool table has a total playing area of about twenty-seven feet; a snooker table’s surface is about seventy-two square feet. What’s more, the pockets on a snooker table are actually smaller—about three and a half inches wide.

But the basic premise of the game is simple. A player uses a cue to strike the white ball in such a way that it will make contact with one of the fifteen red balls, causing the red to roll into a pocket, which earns the player a single point. Then they do the same again, but this time aiming for one of six other colored balls, each worth a different number of points—yellow, green, brown, blue, pink, or the highest-value black ball at seven points. Then it’s back to red. Any time the player fails to make a pot, the break comes to an end, and their opponent gets a turn at the table. When either player racks up a sufficient number of points so that their opponent can no longer draw level, they win the frame; the match ends when one player has won a certain number of frames—best of three, best of seven, or, in the case of the World Snooker Championship final, best of thirty-five.

If this all sounds feasible, or even fun, then I’m afraid my description has been misleading. Faced with a real-life snooker table—unless you’ve already had years of practice—you probably wouldn’t be able to do almost any of the things I’ve just described. Your cue would slip; the cue ball, moving over the gigantic surface of the table, would strike the wrong object or nothing at all; the object ball would careen off in the wrong direction. And of course, when you finally managed to make a single pot, the cue ball would end up in such an awkward position afterward that you wouldn’t stand a chance of making another.

Most mainstream sports, while awe-inspiring at the professional level, also tend to serve as fun and accessible pastimes for amateurs, even young children. Think soccer, tennis, basketball. Snooker declines to lend itself so readily to the amusement of dilettantes. The cultural status of the game stems therefore not from mass participation but from mass viewership. Bad snooker would be painful to watch; mediocre snooker is notoriously boring; but great snooker is sublime. And it is generally agreed that even among those legends of the game who have astonished and delighted the viewing public, one player stands alone.

At his best, Ronnie O’Sullivan conducts his games with something like orchestral splendor, arranging and rearranging the balls across the table’s surface in hypnotically precise passages of play. Each frame becomes a kind of logic puzzle, an intricate question with a thrillingly simple answer, an answer only one person can see. An apparently chaotic jumble slowly reveals its hidden form: the cue ball charts a single path, from red to color and back again, spinning, swerving, ricocheting, or stopping dead as required, until everything is neatly cleared away. No, no, you think, it isn’t possible—and then, rebounding from the right-hand cushion, the red sails over the colossal width of the table and slots down neatly, inevitably, into the minuscule middle left pocket.

Take the last frame of the 2014 Welsh Open final. The footage is available online, courtesy of Eurosport Snooker: if you like, you can watch O’Sullivan, then in his late thirties, circling the table, chalking his cue without taking his eyes from the baize. He’s leading his opponent, Ding Junhui—then at number three in the world snooker rankings—by eight frames to three, needing only one more to win the match and take home the title. He pots a red, then the black, then another red, and everything lands precisely the way he wants it: immaculate, mesmerizing, miraculously controlled.

The last remaining red ball is stranded up by the cushion on the right-hand side, and the cue ball rolls to a halt just left of the middle right-hand pocket. The angle is tight, awkward, both white and red lined up inches away from the cushion. O’Sullivan surveys the position, nonchalantly switches hands, and pots the red ball left-handed. The cue ball hits the top cushion, rolls back down over the table, and comes to a stop, as if on command, to line up the next shot on the black. O’Sullivan could scarcely have chosen a better spot if he had picked the cue ball up in his hand and put it there. The crowd erupts: elation mingled with disbelief. At the end of the frame, when only the black remains on the table, he switches hands again, seemingly just for fun, and makes the final shot with his left. The black drops down into the pocket, completing what is known in snooker as a maximum break: the feat of potting every ball on the table in perfect order to attain the highest possible total of 147 points.

Watch a little of this sort of thing and it’s hugely entertaining. Watch a lot and you might start to ask yourself strange questions. For instance: In that particular frame, after potting that last red, how did O’Sullivan know that the cue ball would come back down the table that way and land precisely where he wanted it? Of course it was only obeying the laws of physics. But if you wanted to calculate the trajectory of a cue ball coming off an object ball and then a cushion using Newtonian physics, you’d need an accurate measurement of every variable, some pretty complex differential equations, and a lot of calculating time. O’Sullivan lines up that shot and plays it in the space of about six seconds. A lucky guess? It would be lucky to make a guess like that once in a lifetime. He’s been doing this sort of thing for thirty years.

Last edited: